Upcoming Event: Men's Basketball versus #20 Clemson on February 14, 2026 at 12 p.m.

2/22/2008 12:00:00 AM | Men's Basketball

By Barry Jacobs

Word had it, there was a promising basketball prospect at all-black John Langston High School just an hour up the road from Durham. A friend got Duke grad Al Newman (Class of 1948) to take a look. And that's how, less by plan than by happenstance, the integration of Duke basketball began.

Newman, who has attended Blue Devil basketball games for 58 years, ran a men's clothing store in Danville, Virginia, the self-proclaimed “Last Capital of the Confederacy.” He helped Duke recruit a trio of football players, and was friendly with Vic Bubas and members of his coaching staff.

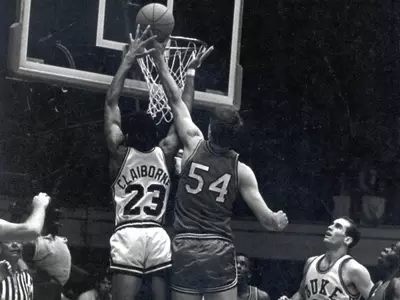

Newman watched slender, 6-2 Claudius Claiborne in action, and immediately phoned Duke assistant Chuck Daly, a particular friend. “Chuck is a clothes horse, that's how we got to know each other,” Newman recalled. Daly came to Danville and watched Claiborne play. “Chuck looked at him for about 60 seconds, and said, ?He could be our sixth man.' ”

Claiborne proved much more than that, and will be honored at halftime of Saturday's game against St. John's for his contribution in crossing the color line in Duke basketball.

"I did something that needed to be done at that time,” Claiborne said. “I was in a position to do it, and it was appropriate, and the experiences at Duke were just what you would have expected them to be, given that place, given the time.”

Claiborne, a senior in 1965, captained both the baseball and basketball teams at Langston High, a sports powerhouse under coach Howard W. “Hank” Allen. Claiborne also was a top student, and earned a prestigious national scholarship. Several of his relatives were teachers, among the few professional routes open to educated African Americans during segregation.

Now new routes opened, if grudgingly, with the admission of black students to previously all-white colleges and universities throughout the South. A civil rights movement swept the country, supported by federal law, forcing changes in statute, custom, and conduct, both public and private. The transition was resisted bitterly in many quarters. Civil rights demonstrators were threatened, arrested, beaten, shot, murdered, particularly although not exclusively in the South.

The Atlantic Coast Conference acquiesced to segregation within its major sports until 1963, when the University of Maryland added Darryl Hill, the first African-American football player to attend a historically white university in the South. A year later, when Claiborne was a high school senior, the Terrapins brought in the white South's first pair of black basketball players, Billy Jones and Julius “Pete” Johnson.

Against this backdrop Claiborne decided not to go to N.C. A&T to play for Cal Irvin, a major figure in the all-black Central (formerly Colored) Intercollegiate Athletic Association. He also spurned Wake Forest and the chance to play for Bones McKinney, an avid suitor. Instead, Claiborne seized an opportunity that had long been denied other African Americans of comparable merit. He chose to attend Duke, a prestigious school just beginning to cultivate a national image.

"No one had ever had this opportunity before, so of course you take the opportunity,” said the softspoken Claiborne, currently a marketing professor at Texas Southern in Houston, Texas. “You don't say no to it.”

Claudia Claiborne, one of C.B. Claiborne's daughters, saw her father's admission to Duke as an ironic form of reverse affirmative action.

"We keep hearing about affirmative action and black people getting whatever, getting stuff because they're black, not because they deserve it,” said the physician. “Whereas, he's the opposite. He should have gotten in by his grades, but if it weren't for basketball he wouldn't have.”

C.B. Claiborne was intrigued by Duke in part because it was successful on the court, and employed a style seemingly compatible with the teachings of Hank Allen.

Back then, white teams tended to embrace a deliberate, patterned approach while their African-American counterparts in leagues such as the CIAA chose a style that resembles the modern game.

"We grew up playing both ends of the court, and it was about pressing defense,” Claiborne said. “The black game, even though it was not always characterized by pressing defenses, I think it's very much characterized by transition, and the game is dominated by transition rather than setup.”

Bubas, a disciple of N.C. State's Everett Case, employed an unusual combination of multiple defenses and a fastbreaking attack. The approach worked -- between 1961 and 1967 his teams had the top winning percentage in the country. His talented Blue Devils finished first in the ACC from 1963 to 1966 and went to Final Fours in 1963, 1964, and 1966. And, in an era prior to the 3-point basket and shot clock, from 1963-66 Duke averaged more than 82 points per game, reaching a peak of 92.5 in 1965.

"I think there were maybe three or four or five programs in the country that you would say were in a very special group that sort of was knocking on the door most all the time ? us, UCLA, Kentucky, Cincinnati,” Bubas said.

Bubas, a masterful administrator, relied on assistants to scout players. So it was hardly surprising that he told United Press International -- which referred to Claiborne as “the Negro cage ace” -- that the unseen prospect was “welcome to come out for the team and compete for a position.”

The ambiguity of Claiborne's standing as an academic scholarship recipient came into play in 1969, when the senior risked banishment from the team and possible arrest to participate in a black student takeover of the administration building. Most African-American athletes eschewed demonstrations lest their athletic scholarships be revoked.

Claiborne matriculated at Duke in 1965-66, just two years after the university admitted its first five black undergraduates. The school hardly rushed to embrace diversity; when Claiborne received his degree in 1969 only eight African-American students preceded him in graduating.

Harold “Bucky” Waters, another Case prot?g? who left Bubas' staff following the '65 season, said Claiborne had the rare qualities required on and off the court to successfully integrate Duke basketball. “The package of C.B. Claiborne, the kid he was, you can't say it was a Jackie Robinson, but clearly the first kid at Duke would be under a microscope just because he was different, and he was the first,” Waters said.

Tom Carmody, coach of the freshman squad in those days of freshman ineligibility, spoke highly of Claiborne once practice began in the fall of 1965. In an interview with the Duke Chronicle, he called the wing “a swift, smooth ball player with a fine outside shot” and “one of the most unselfish players I've ever coached. He is able to accept criticism graciously and is a most coachable boy.”

(Back then, racial sensitivity, in athletics or beyond, was more the exception than the rule. Many coaches referred to players, all players, as “boys.” Given this was a shorthand putdown of adult African-American men, as integration advanced the reference soon vanished from coaching lexicons.)

Claiborne finished sixth in scoring and third in rebounding on an 11-5 freshman squad led by guard Dave Golden and center Steve Vandenberg. There were racial incidents on the road, but, typically, they went unreported. Taunts and other forms of abuse would accompany Claiborne throughout his career, especially when Duke played at the University of South Carolina. But this, too, was accepted with scant comment, including by those in the Blue Devil contingent.

As a sophomore Claiborne appeared in a dozen games, limited early in the season by a torn ligament in his knee. Duke finished 18-9, losing to North Carolina in the finals of the ACC Tournament. Claiborne got his first start on January 3, 1967 in a five-point home win over Penn State for which Bubas suspended nine players, including four starters, for violating team rules. Often he served as a defensive stopper against opponents' big guards.

Claiborne participated more extensively in 1968 on a team that went 22-6, capping the regular season with a triple-overtime home victory over third-ranked North Carolina. Claiborne played a crucial role and his road roommate, reserve forward Fred Lind, was the unlikely hero.

Lind, a longtime public defender who works in Greensboro, N.C., described Claiborne as quiet off the court. “He was studying most of the time,” Lind said. “Both he and I were pretty serious about the studies. We usually brought our books on the road and did a little bit of studying, because you're missing class a lot of times.”

The two remain friends, and Lind said they speak more now about racial issues than they did as roommates. Such silence was common; rare was the white player who engaged an African-American teammate in conversation about the difficulty of his pioneering experience. Thus Lind knew little of the problems Claiborne encountered in class, even apart from conflicts with racist professors.

"When I went in to my first math class, the teacher walked in and started off the class by holding up a book and saying, ?How many of you used this in high school?'” Claiborne recalled. “And I looked around, and everybody had their hand up except me. It was a big book, it was the calculus book that had derivative and integral calculus in it. The first part was derivatives, the second part was integrals. He then said, ?Since all of you had this, we're going to skip the first part and let's start with the second part of the book.'”

Claiborne laughed heartily as he told the story; coming from an intentionally underfunded, underequipped school system, where African-American students received leftovers from whites like youngsters wearing hand-me-downs from older siblings, he was immediately at a competitive disadvantage. He coped.

Black and white teammates who socialized away from the game were even rarer than those who discussed race. “I didn't really hang around with him outside of the basketball,” Lind said of Claiborne. “I'm sure he went to [N.C.] Central.”

In fact, ice-breaking black athletes found there were few social options on overwhelmingly white campuses. Wherever they attended school, they gravitated to the nearest historically African-American college, which for Claiborne and North Carolina's Charles Scott was Durham's N.C. Central University. Claiborne spent so much time there, he had a meal card for the cafeteria.

During the offseason, Scott and Claiborne engaged in pickup games with NCCU players, or went to the outside courts at nearby Hillside High School.

Mixing with Durham's black community, one of the more activist in the South, inevitably drew Claiborne into politics.

Sit-ins and boycotts were employed to combat segregation. The white power structure remained unresponsive. Local government was slow to incorporate African-Americans in its work force or on its advisory boards despite the fact the city was 40 percent black. When it came time to build a freeway, the chosen downtown route destroyed Hayti, a thriving business district dubbed “the black Baltimore.” Some 500 acres were cleared; the area has yet to recover.

Duke succumbed to unrest when, following the April 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., hundreds of students, black and white, engaged in a “Silent Vigil” on the main quad. They peacefully protested the university's discriminatory policies, particularly working conditions for non-academic personnel. Also at issue was President Douglas Knight's continued membership in the segregated Hope Valley Country Club, where Claiborne was excluded when the basketball team held its annual banquet in 1966.

Claiborne appeared in 22 games on a 1969 team that dropped to 15-13 in what proved Bubas' finale as a head coach. The senior enjoyed consecutive strong showings in the late-December Sugar Bowl in New Orleans, and on the year contributed 6.5 points per game, double his scoring average from '68. Yet his playing time diminished as the season progressed.

With little word, Claiborne missed practice and a mid-February trip to West Virginia to face Waters' Mountaineers. Instead he joined other African-American students in occupying Allen Building, Duke's administrative headquarters, a popular form of campus protest at the time.

The occupiers, who did virtually no damage, used the tactic to publicize demands such as the need for meaningful numbers of black faculty, courses in African-American studies, an end to harassment by campus police, and the availability of a barber who would cut their hair.

Protestors left the building before arrests were made. Bubas issued a statement affirming his support for Claiborne and his participation on the team, and the season soon concluded.

Claiborne earned an engineering degree from Duke. He had a postgraduate offer to join the Harlem Globetrotters, but with a wife and young child chose to enter the business world instead. Later he received two master's degrees (from Washington University and Dartmouth College) and a doctorate from Virginia Tech. His academic career, a cross-country journey that spans more than a quarter-century, led Claiborne to Texas Southern, where he is a professor in the business school.

This weekend, his alma mater takes a moment to acknowledge Claiborne for another journey, the step he took as a student-athlete, a step that helped transform Duke's basketball program and the university itself.

Barry Jacobs (Duke, Class of 1972) is the author of “Across The Line, Profiles in Basketball Courage: Tales of the First Black players in the ACC and SEC.”