Hall of Fame Life

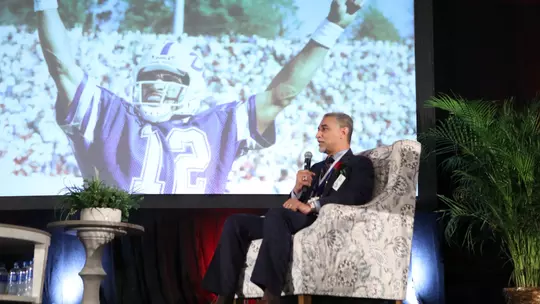

Clarkston Hines still enjoying the fruits of his Duke football labor

Jim Sumner, GoDuke The Magazine

This story originally appeared in the 14.11 Issue of GoDuke The Magazine - June 2023

Clarkston Hines grew up in Chapel Hill but went to high school in Jacksonville, Fla., where he attended the prestigious Bolles School. Around 1984 he and some friends got tickets to a USFL game between the Jacksonville Bulls and the Tampa Bay Bandits.

The Bandits were coached by Steve Spurrier and Hines was amazed with what he saw.

“I remember seeing Coach Spurrier’s offense, throwing the ball all over the field and I was like ‘Wow, would I love to play in an offense like that.’ I had no clue whatsoever that Coach Spurrier had been the offensive coordinator at Duke; I didn’t know my football history at that point. But I was just amazed.”

A few years later Hines was a wide receiver at Duke and Spurrier was his head coach and the combination established records that still stand today. They led to Hines’ induction in the College Football Hall of Fame in 2010 and to his enshrinement in the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame this spring. He had been selected for the Duke Athletics Hall of Fame as soon as he was eligible in 1999, 10 years after he illustrious Blue Devil career concluded.

Before Duke, the 6-foot-1 Hines was a basketball and football star at Bolles. He considered pursuing basketball at the next level until a fateful meeting.

“While I was up in Richmond on an unofficial visit in 1984, I was over at JD Barnett’s house. He was coaching Virginia Commonwealth at the time. And Coach Barnett gave me a compliment, but it was a little backhanded. He said something to the tune of that my jumping ability makes up for my size. So basically he called me short and after that meeting I decided to play football in college instead of basketball. So yeah, I kind of owe that to Coach Barnett and even though it always was my dream was to play college basketball growing up.”

Duke players Terrance Laster and Dewayne Terry were a year ahead of Hines at Bolles and gave positive reviews to Hines. Hines was a superb student and that was an attraction.

“It just made sense to go to a great school like Duke, get a good education and help turn that program around, which we were able to do.”

Steve Sloan was Duke’s head coach when Hines arrived. As a freshman Hines tore up his left ACL in practice, trying to fight for a ball through contact, and missed all of the 1985 season. He barely played in 1986, catching only three passes.

Sloan left Duke after the ’86 season to become director of athletics at his alma mater, Alabama, and Duke replaced him with Spurrier, who took over for the 1987 season.

Hines was in a vulnerable place, injured and with a new coach who had not recruited him and had no investment in him.

But he recalls more excitement than anxiety.

“I had nowhere to go but up. I was still suffering from a lack of confidence. I wasn’t myself yet. I happened to be up in the New York City area when the news broke about Coach Spurrier being hired and I immediately went back in my mind (to that USFL game). I thought of that and the opportunity to play in an offense like that and I made up my mind that I was going to give it everything I had to be able to play receiver in an offense like that.”

Spurrier hired Marvin Brown as his wide receivers coach. Brown had played receiver under Spurrier when he had served as Red Wilson’s offensive coordinator prior to his USFL job, and the two meshed right away.

“He probably was the perfect receivers coach for me because he too had injured his knee and had to come back from that and he taught me important exercises that I needed to do to strengthen my leg. He taught me the concept of ‘Listen, you’re going to have to compensate for your ACL by making your leg as strong as possible.’”

Brown convinced Hines to take a knee brace off his left leg and trust his rehab work. Spurrier says it didn’t take him long to realize he had something special on his hands.

“He quickly became our number one receiver as a guy who was going to have a lot of balls thrown his way.”

Hines exploded as the one the nation’s top wide receivers. He led the ACC in receiving yards in 1987, 1988 and 1989. Prior to 1987 only two ACC receivers had ever hit 1,000 receiving yards in a season. Hines did it three years in a row.

What made Hines so good?

“Just an ability to play,” Spurrier said. “Compete, tough, run great routes, catch everything. I remember when we were playing NC State and he ran a middle route, about 15-16 yards, and he caught it and about three of them hit him right after he caught it. He got up and he shook his shoulders a little bit as if to say ‘You dudes can’t hurt me.’”

It’s easy to frame Hines as a gazelle who operated in space, but he confirms that he loved going over the middle.

“As I look back I don’t know if it was toughness or just mild insanity in terms of how hard you could get hit across the middle, but I never was afraid of running across the middle. Wherever the ball was going, I was going to run there.”

Steve Slayden, Duke’s starting quarterback in 1987, concurs.

“Going over the middle in the ‘80s was different than it is now. Not everyone wanted to do it. He was very graceful, fluid, his hands were great. But he was tough. He was not afraid to go across the middle and get hit.”

In public Spurrier put on an affected, “Aw shucks” persona. Just pitching and catching. But it was nothing of the sort.

“Coach Spurrier’s offense was so well put together,” Hines recalls. “He was excellent at having spacing, creating. ‘Okay, this receiver runs this route to get the safety back but the tight end runs the underneath route and the linebackers leave the route wide open for the middle route.’ I understood spacing to make sure we were going to be open and the quarterback was taught to throw to open spaces which meant we weren’t going to be torn up. It wasn’t simple and what people might have done was to take Coach Spurrier for granted. If you thought of him as this country guy from East Tennessee, not very smart, then that was going to be a problem for you. Take him for granted at your own peril.”

Anthony Dilweg, Duke’s QB in 1988, says Hines was the perfect receiver to exploit Spurrier’s genius.

“He had a great understanding contextually of the game and how it’s played. His strengths as a receiver being a guy who could accelerate and decelerate his speed very intentionally to create space with his defenders. He was fast but he wasn’t elite fast. But he also had a deceptive shake-wiggle to his shoulders to deceive defenders as another way to create space. Whenever I threw to Clarkston I didn’t have to throw a great ball in a tight window because he was so good at creating space. He had soft hands. As a quarterback, you had to love it.”

Slayden and Dilweg add another perspective. Hines’ basketball experience gave him an advanced ability to see the floor and create space, abilities that he translated to the gridiron.

“He absolutely knew how to get open,” Slayden says. “Basketball definitely helped him be a graceful and fluid wide receiver. He could read the defense and run the routes and catch the ball.”

Hines played with four different starting quarterbacks at Duke, Slayden in 1987, Dilweg in 1988, Billy Ray at the beginning of the 1989 season and Dave Brown at the end, after Ray injured his throwing shoulder. Obviously, he worked well with all four.

Hines says the burden wasn’t on him but rather on the quarterbacks to fully master Spurrier’s system.

“What helped me was that the quarterback had to adjust to Coach Spurrier’s offense. It was important for them to understand ‘This is the system’ and we’re going to run things accordingly. There was less adjustment for the receivers and possibly more adjustment for the quarterbacks.”

Dilweg adds that Spurrier’s goal was to make practices so hard for his quarterbacks that games seemed easy.

Hines says the North Carolina games are the ones that stand out, in part because he grew up in Chapel Hill.

“The Carolina wins were extra sweet. If I had to pick one it would have to be ‘89 because it checked off so many things — beating Carolina big, becoming eligible for a bowl game and winning the ACC championship.”

Duke won all three games against Carolina during Spurrier’s tenure as head coach.

Hines had 122, 104 and 162 receiving yards in those three Carolina games.

His best statistical game came two weeks before UNC in 1989, against Wake Forest. This was Brown’s first start at Duke. On the first play from scrimmage Brown audibled and hit Hines for a 76-yard score.

“That first touchdown I remember severely blown coverage. There was nobody around. It made it very easy.”

With about six minutes left in the game and Duke up 45-28 Brown and Hines bettered that, 97 yards, the longest TD pass in Duke history until Sean Renfree and Jamison Crowder went for 99 in 2012 against Miami.

Hines has similar memories of that play — an open field and a perfectly thrown ball.

Duke won that game 52-35, with Brown throwing for 444 yards, 251 to Hines. The duo also connected on a four-yard scoring strike.

Hines’ career high in receptions was 11 (192 yards) in 1987, a 47-45 loss to NC State. Slayden threw an ACC record six touchdown passes in a 48-14 win over Georgia Tech in 1987. Hines caught three of them, one of six games in which Hines had three TD catches.

Hines ended his college career with six receptions for 112 yards in Duke’s 49-21 loss to Texas Tech in the All-American Bowl. It was the last of his 18 games with at least 100 receiving yards.

He had 189 career receptions, 38 of which went for touchdowns. The latter still is an ACC record — and was the NCAA record at the time.

The honors flowed for Hines. He was named first-team All-America and ACC Player of the Year and won the McKevlin Award as the ACC’s top male athlete the following spring. He is one of only three Duke players to be named All-America in two seasons.

The Buffalo Bills drafted Hines ninth in the 1990 NFL Draft but he played sparingly and was cut after the season.

“I wasn’t able to overcome not having an ACL, like I was at college. I wasn’t able to get over the hurdle. I needed two healthy knees to compete at that level.”

Hines did star for the ill-fated Raleigh-Durham Skyhawks, who went 0-10 in their only season in the World League of American Football. Hines had 31 receptions and a team-leading 614 yards for the Skyhawks. That was in 1991.

He had some feelers after that but decided “it was time to take advantage of that degree.” That degree was political science.

Hines started working in human resources for Gambro Health Care, which eventually was absorbed by DaVita. He gradually morphed into HR Vice-President.

“That meant I got to go to all of the meetings with the field vice-presidents. Everybody was expected to come up with ways to become more profitable, to provide better health care. One project in particular was able to help us become a lot more efficient from a staffing standpoint. So my division president started grooming me to one day take over a field vice-president position and that’s what happened.”

Hines spent about 20 years at Gambro/DaVita before leaving for a short-lived job with another health-care company.

“I felt it was time to leave and do something else. I wanted to form my own business and went into real estate.”

PMI was the answer.

Property Management Incorporated is a Utah-based property management company. Hines operates out of Charlotte and lives at nearby Lake Norman. He and his wife Kathy have four adult sons. His franchise concentrates on residential property management.

Awards from his football days have continued to flow with the Hall of Fame selections. The ACC named him one of the 50 best players of its first half century.

“I have a lot of stuff I have no room for — pictures, framed jerseys,” he admits. He puts stuff in China cabinets. His McKevlin Award is displayed in a restaurant Spurrier owns.

This doesn’t mean he doesn’t appreciate the honors.

“As I get older they feel a whole lot more special than when I first got them.”

His induction in the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame in April, a few weeks after his 56th birthday, left him with similar feelings.

“I’m tickled pink. That was a special thing.”

Kind of like his Duke career.

Dedicated to sharing the stories of Duke student-athletes, present and past, GoDuke The Magazine is published for Duke Athletics by LEARFIELD with editorial offices at 3100 Tower Blvd., Suite 404, Durham, NC 27707. To subscribe, join the Iron Dukes or call 336-831-0767.